Translation: A Seduction

Discovering the lyric essay in the sweetbitter act of literary translation.

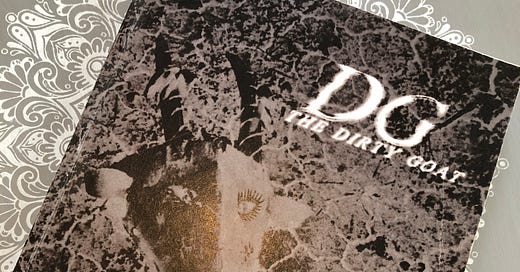

In 2008 I spoke at the American Literary Translators Association conference as part of a panel exploring new metaphors for the translator. Afterwards, the late Joe Bratcher III said, “Kelly, that is the kind of essay we want in The Dirty Goat!” (The journal, which he published for many years, celebrated international literature). I was confused, not yet understanding the diverse ways writers can use a single composition.

“Essay? It’s a panel talk,” I said. A woman I didn’t know gave a response that became a gift to me: “It’s a lyric essay, which is the kind you would write, since you’re a poet.” That was the first I’d heard about lyric essay.

Although I was much delayed in exploring the form, I am enjoying it at last and excited to share its origin in my life. (Essay below first published in Dirty Goat #20, 2009.) I recently read The Extinction of Irena Rey, an evocative and complex novel by the award-winning translator Jennifer Croft, and it took me right back to the time when I was translating poetry—how I loved it!

Opening

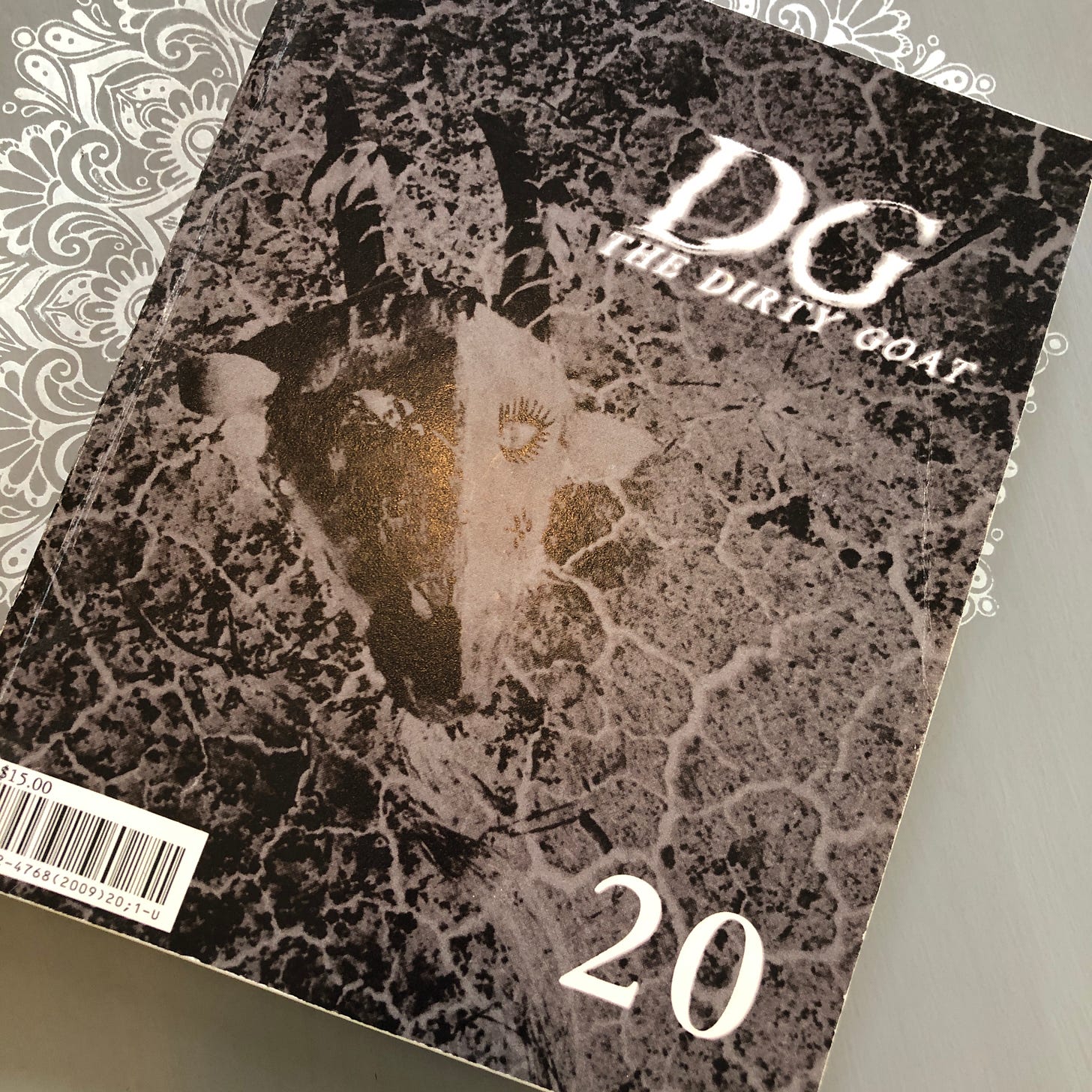

If I had to pick a god or goddess of translation it would be Eros. Anne Carson begins her book Eros the Bittersweet by naming Sappho as the first to call Eros bittersweet. Carson says, “Eros seemed to Sappho at once an experience of pleasure and pain. Here is contradiction and perhaps paradox. To perceive this eros can split the mind in two.”1

What better deity for the dilemma that translators face on every page? Our task is at once irresistible and elusive, delightful and impossible. Sappho2 wrote:

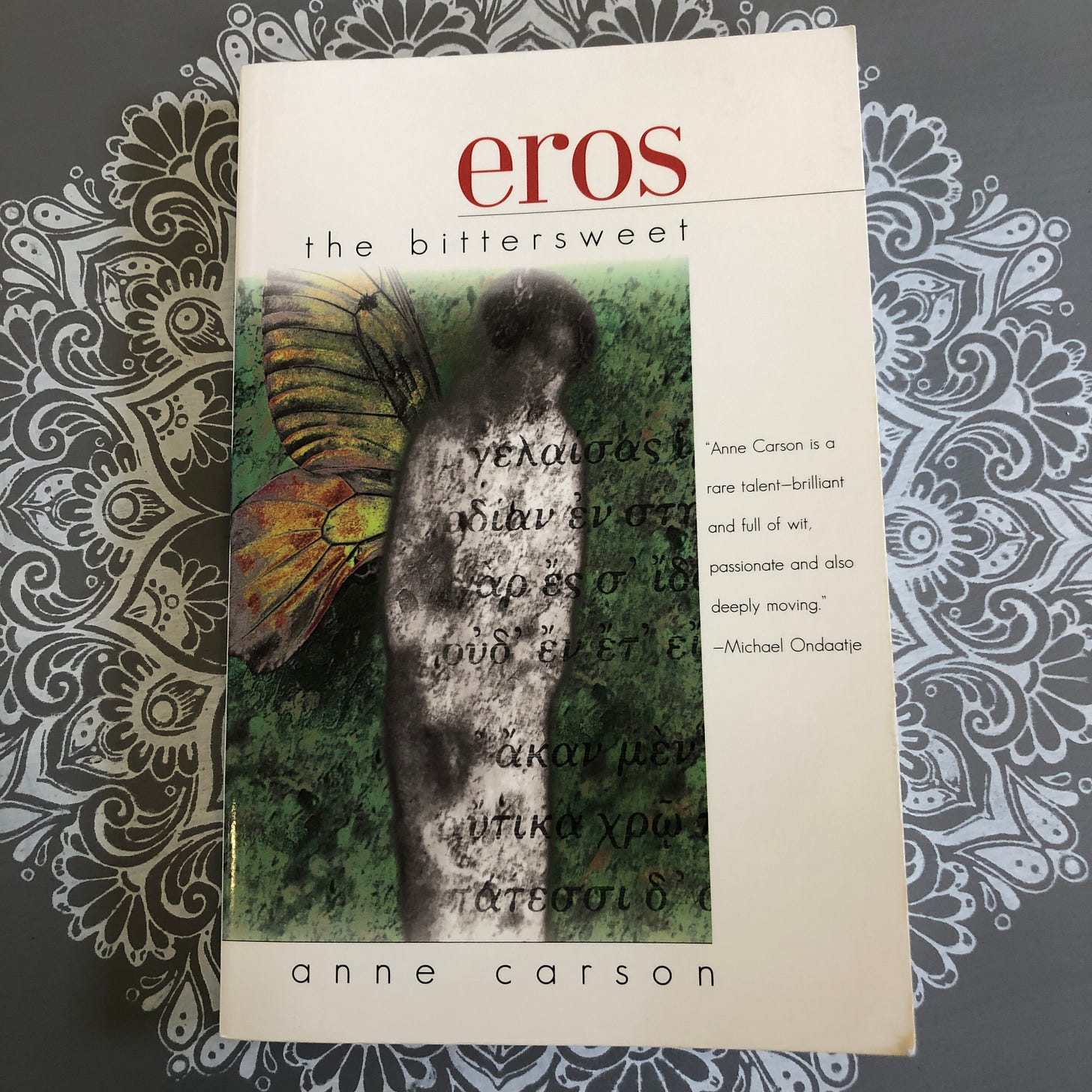

Eros loosener of limbs once again trembles me, a sweetbitter beast irrepressibly creeping in.

The task of translators is often discussed using the imagery of marriage: fidelity or faithfulness to the original, being true to the work. Fidelity has been translation’s yardstick for centuries. A new metaphor for what translators engage in overlaps with, but is distinct from, marriage: the act of seduction. I am speaking of mutual seduction: the poem or story or novel or play must seduce the translator into engaging with single-minded focus and energy, and the translator must seduce the spirit of the piece into a new language.

Inspired by Carson, I’ll explore this metaphor using some of Sappho’s fragments, in translations by Mary Barnard and by Willis Barnstone. Their fragmentary nature will, I hope, underline that edge of desire not yet fulfilled upon which seduction depends.

That Look in Her Eye

I have been researching seduction. It is difficult to do online—so much extraneous material—so I’ve been taking notes, interviewing friends willing to talk. There is general agreement that seduction begins with some form of attraction. Whether wit, or voice, or shape, or intellect, or some ineffable energy, there is something about a person that catches our attention, causes us to stop, take a second look, a third…3

Without warning As a whirlwind swoops on an oak Love shakes my heart

Translators may speak of undertaking a translation because an encounter with a particular novel or poem or book of poetry in its original language sparked the desire to bring it into English.

The Belorussian poet Valzhyna Mort commented, with respect to her translations of Polish, Russian, and English poets: “That was my manifestation of loving a poet—I wanted to own it, I wanted the poem to be mine, and the only way was to translate it.”4

You came and I went mad about you. You cooled my mind burning with longing.

The Dance5

So we engage. We read and reread. We sit down with dictionary, thesaurus, the original text—and a keyboard or fat pad of paper. We begin. It doesn’t take long to arrive at that point in the process where translators find ourselves resorting to talk of target language, of wrestling with or conquering the text—language of control.

Classical metaphors for the experience of Eros include, as Carson points out, metaphors of war, of assault and resistance.6 So it is with translation. Struggling with an image or idiom that we just can’t seem to express in English, there comes the desire to bend the text to our own will, just to get shet of the thing.

Here, the notion of seduction can save us. An enticing must take place. To force seduction is to rape. We must instead engage in a subtle dance, moving a little nearer, a little further away, but always with the hope of ending up closer.

And just as we cannot be too forceful, nor should we be too serious. Rigidity is not compatible with creativity, and literary translation is nothing if not a creative act. So it is important to maintain a sense of playfulness.7

Now, while we dance, Come here to us gentle Gaity, Revelry, Radiance and you, Muses with lovely hair

The Unbluntable Edge

Carson describes Eros as “an issue of boundaries. He exists because certain boundaries do. In the interval between reach and grasp, between glance and counterglance… the absent presence of desire comes alive…[the] inevitable boundary that creates Eros [is] the boundary of flesh and self between you and me. And it is only, suddenly, at the moment when I would dissolve that boundary, I realize I never can.”8

A translator is all too familiar with such a boundary. They know the original intimately—an intimacy that intensifies while composing the translation—yet must accept the gap, the boundary, between that original and anything they can produce. “Pleasure and pain at once register upon the lover,” Carson notes.9 We may think of giving up entirely, of giving into the despair that too often follows an encounter with Eros.10

I don’t know what to do. I think yes—and then no

Encouragement

Again, seduction must be mutual to be successful. There must be signs that the poem will yield to the translator even as the translator yields to the poem. For the translator, this yielding is a subversion of ego: she must be willing to release her customary surroundings of French wine, soft jazz, and silk sheets, and be open to new experiences of microbrew, acoustic blues, and a futon. As with other acts of devotion, that of the seducer/translator risks loss of identity.

Similarly, a poem must have a strong enough identity that its images can be shifted a little this way or that—its “drinking” may become “sipping,” its “walking” may need to be called “strolling”—so that its music can also carry over into a new language.

To succeed, a translator must be willing to be taken to unexpected places, to surrender control and certainty of outcome. We must be willing to explore in the dark and to love what we find. Keats’ negative capability is a critical resource of the translator. We must engage without knowing whether we’ll end up with something we’re willing to put our name to. It is not for the faint of heart.11

If you are squeamish Don’t prod the beach rubble

Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet (1986; Dalkey Archive, 1998) 3.

Sappho, Sweetbitter Love: Poems of Sappho, trans. Willis Barnstone (Boston: Shambhala, 2006) 101.

Sappho, Sappho, trans. Mary Barnard (Boston: Shambhala, 1994) 63.

Kevin Nance, “You Cannot Tell This to Anybody,” Poets and Writers May/June 2008: 31.

Substack doesn’t allow footnotes in poetry blocks so I am placing them just before or just after the Sappho passages. The one above: Barnstone 85.

Carson 39.

Barnard 23.

Carson 30.

Carson 30,

Barnstone 83.

Barnard 95.

Amazing. Ownership, desire for--connection, conversation with the original. I love this explorations.